Pieces of Khet, a popular laser chess-like game.

[Epistemic Status: Taking Phenomenology Seriously – Allowing Myself to Speculate Profusely]

Introduction: Laser Chess as a Metaphor for the Brain as a Non-Linear Optical Computer

In Laser Chess (a synecdoche for games of this sort), players arrange various kinds of pieces that interact with lasers on a board. Pieces have “optical features” such as mirrors and beam splitters. Some pieces are vulnerable to being hit from some sides, which takes them off the board, and some have sides which don’t interact with light but merely absorb it harmlessly (i.e. shields). You usually have a special piece which must not be hit, aka. the King/Pharaoh/etc. (or your side loses). And at the end of your turn (once you’ve moved one of your pieces) the laser of your color is turned on, and its light comes out of one of your pieces in a certain direction and then travels to wherever it must (according to its own laws of behavior). Usually when your laser hits an unprotected side of a piece (including one of your own pieces), the targeted piece is removed from the board. Your aim is to hit and remove the special piece of your opponent.

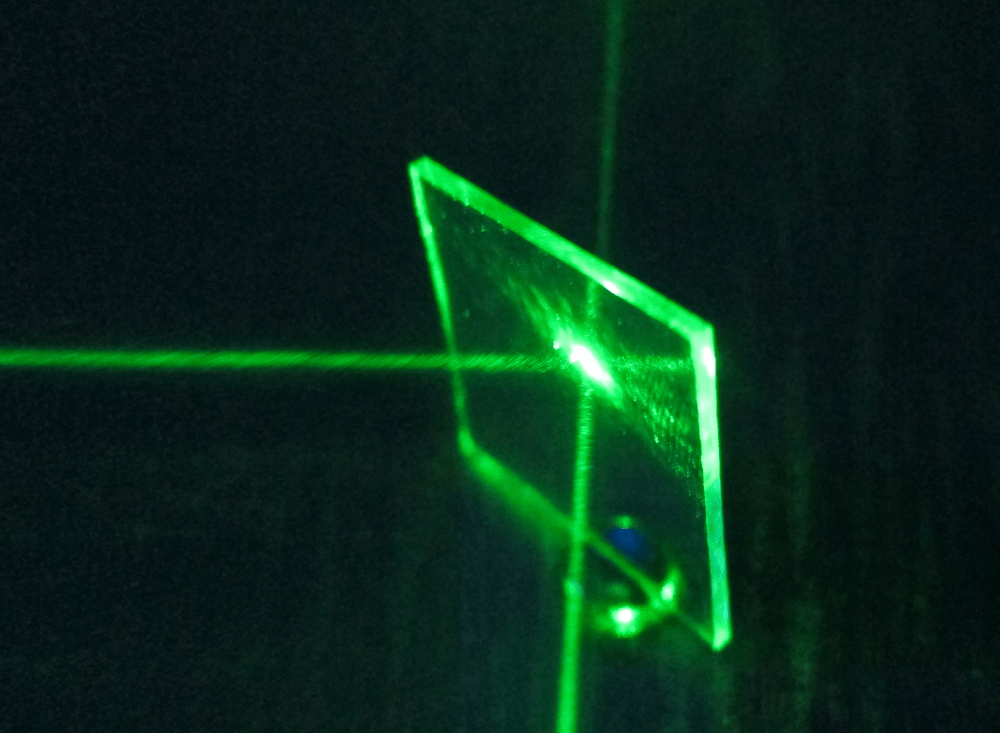

Example of a beam splitter optical element (source)

What makes this game conceptually more interesting than Chess isn’t just that its openings haven’t been thoroughly studied (something Bobby Fischer complained about with Chess), but rather that the light’s path depends on all pieces functioning together as a whole, adding a layer of physical embodiment to the game. In other words, Laser Chess is not akin to Chess 960, where the main feature is that there are so many openings that the player needs to rely less on theory and more on fluid visual reasoning. It’s more, at least at the limit, like the difference between a classical and a quantum computer. It has a “holistic layer” that is qualitatively different than the substrate upon which the game normally operates.

In Laser Chess, the “piece layer” is entirely local, in that pieces can only move around in hops that follow local contextual rules. Whereas the “laser layer” is a function of the state of the entire board. The laser layer is holistic in nature because it is a function of the entire board at once. It’s the result of, at the limit, letting the light go back and forth an infinite number of times and let it resolve whatever loop or winding path it may need to go through. You’re looking for the standing wave pattern the light wants to resolve on its own.

Online Laser Chess (source) – the self-own of the blue player is understandable given the counter-intuitive (at first) way the light ends up traveling.

In Laser Chess you move your piece to a position you thought was safe just to be hit by the laser because the piece itself was what was making that position safe! The beginner player is often startled by the way the game develops, which makes it fun to play for a while. The mechanic is clever and to play you need to think in ways perhaps a bit alien to a strict Chess player. But at the end of the day it’s not that different of a game. You do end up using a lot of calculations (in the traditional Chess sense of “mental motions” you keep track of to study possible game trees), and the laser layer only changes this slightly.

When the laser beam hits one of the mirrors, it will always turn 90 degrees, as shown in the diagrams. The beam always travels along the rows and columns; as long as the pieces are properly positioned in their squares, it will never go off at weird angles.

– Khet: The Laser Game Game Rules

In Laser Chess, the behavior of light is not particularly impressive. After all, thinking about the laser layer in terms of simple local rules is usually enough (“advance forward until you hit a surface”, “determine the next move as a function of the type of surface you hit”, etc.). The game is quite “discretized” by design. Tracing a single laser path is indeed easy when the range of motion and possible modes of interaction are precisely constructed to make it easy to play. It’s uncomplicated by design. The calculations needed to predict the path of the light never becomes intractable: the angles are 45°/90° degrees, the surfaces cleanly double, reflect, absorb the light, etc.

Laser Chess, now with weird polygonal pieces and diffraction effects!

But in a more general possible version of Laser Chess the calculations can become easily intractable and far more interesting. If we increase the range of angles the pieces can be at relative to each other (or make them polygons) we suddenly enter states that require very long calculations to estimate within a certain margin of error. And if we bring continuous surfaces or are allowed to diffract or refract the light we will start to require using the mathematics that have been developed for optics.

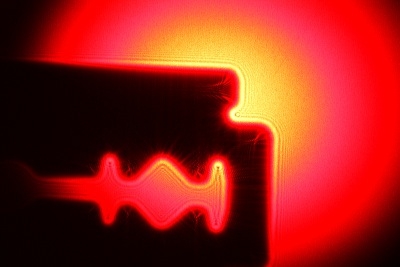

Edge diffraction (source)

In a generalized Laser Chess, principles for the design of certain pieces could use specific optical properties, like edge diffraction:

If light passes near the edge of a piece (rather than hitting it directly), it could partially bend around the object instead of just stopping. Obstacles wouldn’t provide perfect shadows, allowing some light to “leak” around corners in a predictable but complex way. Example: A knight-like piece could have an “aura of vulnerability” where light grazing its edge still affects pieces behind it.

Instead of treating lasers as infinitely thin lines, beams could diffract when passing through narrow gaps or slits. This would allow for beam broadening, making it possible to hit multiple pieces even if they aren’t in a direct line. Example: If a piece has a slit or small hole, it could scatter the laser into a cone, potentially hitting multiple targets.

And so on. And there is a staggering number of optical properties to select from. From refraction, iridescence, polarization, birefringence, and total internal reflection, each offering unique strategic possibilities. And then there we also have their mutual interactions to consider. Taking all of this into account, a kind of generalized Laser Chess complexity hierarchy arises:

- The simplest Laser Chess variants are mostly geometric, with straightforward ray tracing. They benefit from a physical laser or a computer, but don’t require it.

- Intermediate complexity comes after adding diffraction, refraction, and wave optics, requiring Fourier transforms and wave equations to analyze the beam behavior. It requires a physical laser or a computer to be played, because mental calculation won’t do.

- And high complexity variants come about when you take into account quantum-inspired effects like interference and path integrals, leading to both deterministic and probabilistic gameplay mechanics where players need to take into account complex superpositions and calculate probabilities. It requires either carefully designed cases for computers to be sufficient; physical embodiment might become necessary above a certain complexity.

The Self as King

Let’s start to draw the analogy. Imagine the special piece as your sense of self, the piece that must be protected, while the other pieces represent state variables tuning your world-model. In some configurations, they work together to insulate the King, diffusing energy smoothly across the board. In others, a stray beam sneaks through—an unexpected reflection, a diffraction at just the wrong angle—and suddenly, the self is pierced, destabilized, and reconfigured. The mind plays this game with itself, setting up stable patterns, only to knock them down with a well-placed shot.

The field of consciousness, poetically speaking, is a lattice of light shifting under the pressure of attention, expectation, and the occasional physiological shear. But whether or not the awareness that corresponds to the light is self-aware depends on the precise configuration of this internal light path: some ways of arranging the board allow for a story to be rendered, where a sense of self, alive and at the center of the universe, is interpreted as the experiencer of the scene. Yet the scene is always being experienced holistically even if without a privileged center of aggregation of the light paths. The sense of a separate, divided witness might be a peculiar sleight of hand of this optical system, a kind of enduring optical illusion generated by what is actually real: the optical display.

BaaNLOC

The Brain as a Non-Linear Optical Computer (BaaNLOC) proposes that something like this happens in the brain. The brain’s physical structure – its neural wiring, synaptic connections, and the molecular machinery of neurons – maps onto a set of “optical” properties. These properties shape how electromagnetic waves flow and interact in neural tissue.

Think of a sensory stimulus, within the Laser Chess analogy of the brain’s computational substrate, as akin to a brief blip from a laser. As the stimulus-triggered electrochemical signal propagates through neural circuits, its path is shaped by the brain’s “optical” configuration. Excitatory and inhibitory neurons, tuned to different features, selectively reflect and refract the signal. The liquid crystal matrix encoded in the molecular structure of intracellular proteins might also play a role, perhaps modulating the electromagnetic medium through which the signal must travel.

Where these signals meet, they interfere, their wave properties combining to amplify or cancel each other out. BaaNLOC posits that the large-scale interference pattern and the non-linear emergent topological structure of these interacting waves constitutes the contents of subjective experience.

Attention and expectation act as a steady pressure on this system, stabilizing certain wave patterns over others, like a piece the board influencing the path of the laser. What we perceive and feel emerges from the EM standing waves shaped by this top-down influence.

Psychedelics and BaaNLOC

Psychedelics, in this framework, temporarily alter the optical properties of the brain. Abnormal patterns of signaling elicited by drugs like DMT change how neural waves propagate and interact. The result is a radical reconfiguration of the interference patterns corresponding to conscious experience.

The BaaNLOC paradigm seeks to bridge the brain’s electrodynamics with the phenomenology of subjective experience by framing neural processes in terms of EM wave dynamics and electrostatic field interactions. While the precise mapping between neural activity and optical properties remains an open question (we have some ideas), the process of searching for this correspondence is already generative. The brain’s electrostatic landscape is not uniform; instead, it consists of regions with varying permittivity and permeability, which affect the way EM waves propagate, reflect, and interfere. Axonal myelination influences conduction velocity by altering the dielectric properties of neural pathways, shaping the timing and coherence of signals across brain regions. Dendritic arbor geometry sculpts synaptic summation, forming local electrostatic gradients that influence how waves superpose and propagate. Cortical folding affects field interactions by modulating the spatial configuration of charge distributions, altering the effective permittivity of different regions and creating potential boundaries for wave interference. These parameters suggest that experience may be structured not only by firing patterns but also by the electrostatic properties of the substrate itself. If perception is mediated by standing waves in an EM field shaped by the brain’s own internal dielectric properties, then the phenomenology of experience may correspond to structured resonances within this medium, much like how lenses manipulate light by controlling permittivity gradients. Investigating these interactions could illuminate the connection between the brain’s physical substrate and the emergent contours of conscious experience.

You can even do spectral filtering of images with analogue Fourier transforms using optical elements alone. Think about how this optical element could be used right now in your brain to render and manufacture your current reality:

Analogue Fourier transform and filtering of optical signals. (Gif by Hans Chiu – source).

Real-time analog Fourier decomposition of sensory information would be a powerful computational tool, and we propose that the brain’s optical systems leverage this to structure our world-simulation.

In this framework, certain gestalt patterns act as energy sinks, analogous to standing waves at resonant frequencies. These patterns serve as semantic attractors in the brain’s harmonic energy landscape, forming local minima where perceptual content naturally stabilizes. These attractor surfaces are often semi-transparent, refractive, diffractive, or polarizing, vibrating in geometry-dependent ways. “Sacred geometry” corresponds to vibratory patterns that are maximally coherent across multiple layers at once, representing low-energy states in the system’s configuration space. When the world-sheet begins to resemble these structures, it “snaps” into symmetry, as this represents an energy minimum. This aligns with Lehar’s field-theoretic model of perception, where visual processing emerges from extended spatial fields of energy interacting according to lawful dynamics. Given that such self-organizing optical behavior is characteristic of liquid crystals, it is worth considering whether the brain’s substrate exploits liquid-crystalline properties to facilitate these energy-minimizing transformations.

It is within this paradigm that the following idea is situated.

DMT Visuals as Holographic Cel Animation in a Nonlinear Optical Medium

DMT visuals (and to a lesser extent those induced by classic psychedelics in general) might be understood as semi-transparent flat surfaces in a non-linear optical medium, akin to the principles behind cel animation. Source: How It’s Made | Traditional Cel Animation*

Cel animation uses partially transparent layers to render objects in a way that allows them to move independent of each other. In cel animation the features of your world are parsed in a suspiciously anthropomorphic way. If you change a single element in an unnatural way, you find it rather odd. Like it breaks the 4th wall in a way. You can get someone to blink an eye or move their mouth in the absence of any other movement. What kind of physical system would do that? One that was specifically constructed for you as an interface.

Imagine a child flipping through a book of transparent pages, each containing a fragment of a jaguar, a palm, a tribal mask. As the pages overlay, the scene assembles itself — not as a static image, but as a living tableau (somebody please fire the Salesforce marketing department for appropriating such a cool word). Now imagine those transparencies aren’t merely stacked; they are allowed to be at odd angles relative to each other and to the camera:

This is the basic setup. The idea is that on DMT, especially during the come-up at moderate doses (e.g. reaching Magic Eye-level), the sudden appearance of 2D gestalts in 3D (which are then “projected” to a 2.5D visual field) is a key phenomenological feature. The rate of appearance and disappearance of these gestalts is dose-dependent, same as the kind of interactions they come enabled with. From here, we can start to generalize this kind of system to better capture visual (and somatic, as we will see) features of a DMT experience in its full richness and complexity. Just as in the case of Laser Chess, where we began with a basic setup and then explored how non-linear optics would massively complicate the system as we introduce interesting twists, here as well we begin with cel animation planes in a 3D space and add new features until they get us somewhere really interesting.

An important point is that DMT cel-animation-like phenomenology seems to have some hidden rules that are difficult to articulate, let alone characterize in full because it interacts with the structure of our attention and awareness. Unlike actual cel animation, the flat DMT gestalts don’t require a full semi-transparent plane to come along with them – they are “cut” already, and yet somehow can “float” just fine. Importantly, even when you have extended planes and they are, say, rotating, they can often intersect. Or rather, the fact that they overlap in their position in the visual field does not mean that they will interact as if they were occupying the same space. Whether two of these gestalts interact with each other or not depends on how you pay attention to them. There is a certain kind of loose and relaxed approach to attention where they all go through each other, as if entirely insubstantial. There is another kind of way of attending where you force their interaction. If you have seven 2D gestalts floating in your visual field, by virtue of the fact that you only have so many working memory slots / attention streams, it is very difficult to keep them all separate. At the same time, it is also very difficult to bring them all together. More typically, there is a constantly shifting interaction graph between these gestalts, where depending on how emergent attention dynamics of the mind go, clusters of these gestalts end up being simultaneously being payed attention to, and thus blend/unify/compete and constructively/destructively interfere with one another.

One remarkable property of these effects is that 2D gestalts can experience transformations of numerous kinds: shrinking, expanding, shearing, rotating, etc. Each of these planes implicitly drags along a “point of view”. And one of the ways in which they can interact is by “sharing the same point of view”.

Cels as Planes of Focus

One key insight is that the 2D surfaces that make up these cels in the visual field on a moderate dose of DMT seem to be regions where one can “focus all at once”. If you think of your entire visual field as an optical display that can “focus” on different elements on a scene, during normal circumstances it seems that we are constrained to focusing on scenes one plane at a time. Perhaps we have evolved to match as faithfully as possible the optical characteristics of a camera-like system with only one plane of focus, and thus we “swallow in” the optical characteristics of our eyes and tend to treat them as fundamental constraints of our perception. However, on DMT (and to a lesser extent other psychedelics) one can see multiple planes “in focus” at the same time. Each of these gestalts is typically perfectly “in focus” and yet with incompatible “camera parameters” to the other planes. This is what makes, in part, the state feel so unusual: there is a sense in which it feels as if one had multiple additional pairs of eyes with which to observe a scene.

A simple conceptual framework to explain this comes from our work on psychedelic tracers. DMT, in a way, lets sensations build up in one’s visual and somatic field: one can interpret the multiple planes of focus as lingering “focusing events” that stay in the visual field for much longer, accumulating sharply focused points of view in a shared workspace of visual perspectives.

Another overall insight here is that each 2D gestalt in 3D space that works as an animation cel is a kind of handshake between the feed from each of our eyes. Conceptually, our visual cortex is organized into two hierarchical streams with lateral connections. Levels of the hierarchy model different spatial scales, whereas left-vs-right model the eye from which the input is coming from. At a high-level, we could think of each 2D cel animation element as a possible “solution” for stable attractors in this kind of system: a plane through which waves can travel cuts across spatial scales and relative displacements between the image coming from each eye. In other words, the DMT world begins to be populated by possible discrete resonant mode attractors of a network like this:

The Physics of Gestalt Interactions

As the 2D cels accumulate, they interact with one another. As we’ve discussed before, our mind seems to have an energy function where both symmetrical arrangements and semantically recognizable patterns work as energy sinks. The cel animation elements drift around in a way that tries to minimize their energy. How energized a gestalt is manifests in various ways: brightness of the colors, speed of moment, number of geometric transformations applied to it per second, and so on. When “gestalt collectives” get close to each other, they often instantiate novel coupling dynamics and intermingle in energy-minimizing ways.

Holographic Cel Animation

Since each of the cels in a certain sense corresponds to a “plane of focus” for the two eyes, they come with an implicit sense of depth. As strange as it may sound, I think it is both accurate and generative (or at the very least generative!) to think of each cel animation element as a holographic display.

(source)

I think this kind of artifact of our minds (i.e. that we get 2D hologram-like interacting hallucinations on DMT) ultimately sheds light on the medium of computation our brain is exploiting for information processing more generally. Our mind computes with entire “pictures” rather than with ones and zeros. And the pictures it computes with are optical/holographic in nature in that they integrate multiple perspectives at once and compress entire complex scenes into manageable lower dimensional projections of them.

Each cel animation unit can be conceptualized as a holographic window into a specific 3D scene. This connects to one of the striking characteristics of these experiences. In the DMT state, this quality manifests as a sense that the visualized content is “not only in your mind” but represents access to information that exists beyond the confines of personal consciousness. The different animated elements appear to be in non-local communication with one another, as if they can “radio each other” across distances. At the very least their update function seems to rely both on local rules and global “all-at-once” holistic updates (much akin to the way the laser path changes holistically after local changes in the location of individual pieces).

This creates the impression that multiple simultaneous narratives or “plots” can unfold at “maximum speed” concurrently. Each element seems capable of filtering out specific signals from a broader field of information, tuning into particular frequencies while ignoring others. The resulting 2.5D/3D interface serves as a shared context where gestalts that communicate through different “radio channels” can nonetheless interact coherently with each other in a shared geometric space.

Credit: (smallfly?) (read more)

The above VR application being developed by Hugues Bruyere at DPT (interesting name!) reminded me of some of the characteristic visual computation that can take place on DMT with long-lasting holographic-like scenes lingering in the visual field. By paying attention to a group of these gestalts all at once, you can sort of “freeze” them in space and then look at them from another angle as a group. You can imagine how doing this recursively could unlock all kinds of novel information processing applications for the visual field.

Visual Recursion

Each cel animation element can have a copy of other cel animation elements seen from a certain perspective within it.

Because each animation cel can display an entire scene in a hologram-like fashion, it often happens that the scenes may reference each other. This is in a way much more general than typical video feedback. It’s video feedback but with arbitrary geometric transformations, holographic displays, and programmable recursive references from one feed to another.

The Somatic Connection

(Source)

One overarching conceptual framework we think can help explain a lot of the characteristics of conscious computation is the way in which fields with different dimensionalities interact with one another. In particular, we’ve recently explored how depth in the visual field seems to be intimately coupled with somatic sensations (see: What is a bodymind knot? by Cube Flipper, and On Pure Perception by Roger Thisdell). This has led to a broad paradigm of neurocomputation we call “Projective Intelligence“:

The projective intelligence framework offers a conceptual foundation for how to make sense of the holographic cels. Our brains constantly map between visual (2.5D) and tactile (3D) fields through projective transformations, with visual perceptions encoding predictions of tactile sensations. This computational relationship enables the compression of complex 3D information into lower dimensions while highlighting patterns and symmetries (think about how you rotate a cube in space in order to align it with the symmetries of our visual field: a cube contains perfect squares, which becomes apparent when you project it onto 2D in the right way).

In altered states like DMT experiences, these projections multiply and distort, creating the characteristic holographic windows we’re discussing: multiple mappings occur between the same tactile regions and different visual areas. This explains the non-local communication between visual elements, as the visual field creates geometric shortcuts between tactile representations using the visual field. It’s why separated visual elements appear to “radio each other” across distances: they can be referencing the same region of the body!

The recursive qualities of these holographic cels emerge when the “branching factor” of projections increases, creating Indra’s Net-like effects where everything reflects everything else. The binding relationships that arise in those experiences can generate exotic topological spaces: you can wire your visual and somatic field together in such a way that the geodesics of attention find really long loops involving multiple hops between different sensory fields.

In brief, consciousness computes with “entire pictures” which can interact with each other even if they have different dimensionalities – this alone is one of the key reasons I’m bullish on the idea that carefully depicting psychedelic phenomenology will open up new paradigms of computation.

Collective Intelligence Through Transformer-like Semantics

In addition to the geometric holographic properties of these hallucinations, the semantic energy sink also operate in remarkably non-trivial ways. When two DMT patterns interact, they don’t just overlap or blend like watercolors. They transform each other in ways that look suspiciously like large language models updating their attention vectors. A spiral might encounter a lattice, and suddenly both become a spiral-lattice hybrid that preserves certain features while generating entirely new ones. If you’ve played with AI image generators, you’ve seen how combining prompt elements creates unexpected emergent results. DMT visuals work similarly, except they’re computing with synesthetic experiential tokens instead of text prompts. A hyperbolic jewel structure might “attend to” a self-dribbling basketball, extracting specific patterns that transform both objects into something neither could become alone.

Some reports suggest that internalizing modern AI techniques before a DMT trip (e.g. spending a week studying and thinking about the transformer architecture) can power-up the intellectual capacities of “DMT hive-minds”. If your conceptual scheme can only make sense of the complex hallucinations you’re witnessing on ayahuasca through the lens of divine intervention or alien abductions, the scenes that you’re likely to render will be restricted to genre-conforming semantic transformations that minimize narrative free energy. But if you come in prepared to identify what is happening through the lens of non-linear optics and let the emergent subagents (clusters of gestalts that work together as agentive forces) self-organize as an optical machine learning system, you may end up summoning novel (if still very raw and elemental) kinds of conscious superintelligences.

Conclusion: The Gestalt Amphitheater

In ordinary consciousness, we meticulously arrange our perceptual pieces to protect the King (our sense of self) ensuring that the laser of awareness follows predictable, habitual paths. The optical elements of our world-simulation are carefully positioned to maintain the stable fiction that we are unified subjects navigating an objective world.

DMT radically rearranges these pieces, creating optical configurations where “the light of consciousness” reflects, refracts, and diffracts in unexpected ways. The laser no longer follows familiar paths but moves along a superposition of paths through the system in patterns that reveal the constructed nature of the central self and of the simulation as a whole. The King (that precious sense of being a singular perceiver) stands exposed as what it always was: not an ontological primitive but an emergent property of a particular configuration where “attention field lines converge.”

The projective intelligence framework helps us understand this phenomenology. Our brains constantly map between visual (2.5D) and tactile (3D) fields through transformations that encode predictions and compress complex information. In DMT states, these projections multiply and distort, creating “holographic windows” where multiple mappings occur simultaneously. This explains the non-local communication between visual elements: separated gestalts appear to “radio each other” across distances because multiple tactile sensations can use the visual field as a shortcut to resonate with each other and vice versa.

The emergent resonant attractors of the whole system involve many such shortcuts. When the recursive projections find an energy minima they lock in place, at least temporarily: the complex multi-sensory gestalts one can experience in these states capture layers of recursive symmetry as information in sensory fields is reprojected back and forth, each time adapting to the intrinsic dimensionality of the field onto which it is projected. “Sacred geometry” objects on DMT are high-valence high-symmetry attractors of this recursive process.

The DMT state doesn’t “scramble consciousness” (well, not exactly); rather, it reconfigures its optical properties, allowing us to witness the internal machinery that normally remains hidden in our corner of parameter space. These visuals aren’t “hallucinations” in any conventional sense. That would imply they’re distortions of some more fundamental reality. Instead, I think they’re expressions of our brain’s underlying optical architecture when highly energized and fragmented, temporarily freed from the sensory constraints that normally restrict our perceptual algorithms.

By understanding the brain as a kind of non-linear optical computer, and consciousness as a topologically closed standing wave pattern emergent out of this optical system, we may develop more sophisticated models of how the brain generates world simulations. And perhaps one day (soon!) even discover new computational paradigms inspired by the way our minds naturally process information through multiple holographic dimensional interfaces at once. Stay tuned!

*animations made with the help of Claude 3.7, when otherwise not specified.

Tags

Consciousness, Psychedelic, Neuroscience, Phenomenology, BaaNLOC, Visual Perception